My Journey with Mabel

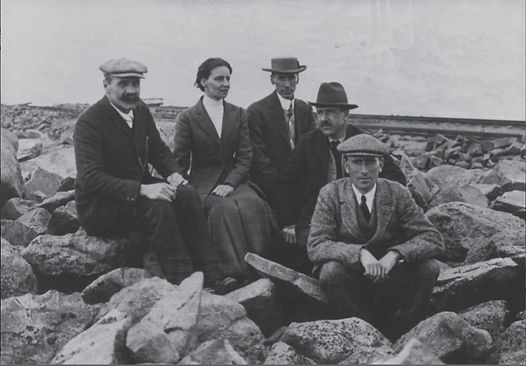

Mabel with J.S. Haldane, E.C. Schneider, Y. Henderson and C.G. Douglas on top of Pikes Peak 14,115 feet, Colorado, 1911.

I gingerly opened the box, expecting to find folders with sheets of paper tucked inside covered with neatly written correspondence, all in chronological order. I peeked under the lid and caught my breath. Hundreds of tiny squares of paper folded numerous times over and bearing scrawled writing that was not only illegible but often crossed itself perpendicularly, my first introduction to the paper-saving and eye-searing mess known as cross-writing. I am an American scientist. What in the world was I doing in the sacred bowels of the Bodleian Library at Oxford University, timidly exploring an uncatalogued archive dating as far back as the early 18th century?

I was following the advice of a man many consider the father of modern respiratory physiology, Dr. John West. After giving a talk on the 100th anniversary of a medical research expedition to Pikes Peak in Colorado, John lamented the fact that very little was known about the lone woman scientist on the 1911 research trip. Mabel Purefoy FitzGerald’s resulting publication was the first to show how people adapt to living at high altitudes. Having just left my university position, I was eager for a new project and John knew just how to set the hook.

“Her archive is at the Bodleian Library in Oxford,” he told me. “It’s a fascinating jumble of what appear to be old hat boxes containing all of her personal and professional papers.”

Being a bit of a bibliophile, the words - Bodleian Library and Oxford (and for no discernable reason - hat boxes) - had me instantly captivated. So here I was, staring at one of forty boxes containing more than one hundred haphazardly packed documents dating anywhere from the early 1700s to 1973. As far as I could tell, organizational attempts had not progressed further than sweeping everything into boxes; letters, graphs, small books, photographs, paper clips, tacks, and even hand-knitted baby mittens.

I began to carefully unfold random packets of papers and read. A chatty letter from a sister-in-law. A letter from Mabel’s grandmother. A letter from Sir Charles Sherrington, Nobel Prize Laureate. A letter from Alfred Lord Tennyson. A letter from the Father of Modern Medicine, Sir William Osler. A letter about dinner with “George Elliot” and Mr. Lewes. A manuscript showing the origin of hydrochloric acid in the stomach. A letter about a casual lunch with Eleanor Roosevelt.

After a stunned moment or two, I decided that Mabel’s story may be worth a second look and possibly of interest to others. Eleven years later (and three new eyeglass prescriptions), I have uncovered the story not only of a woman scientist locked in a lifelong and often ludicrous struggle to become a physician more than a century ago but an extraordinary tale of privilege, hardship, discrimination, shocking perseverance, extraordinary friendships, success, failure, and grand adventure.